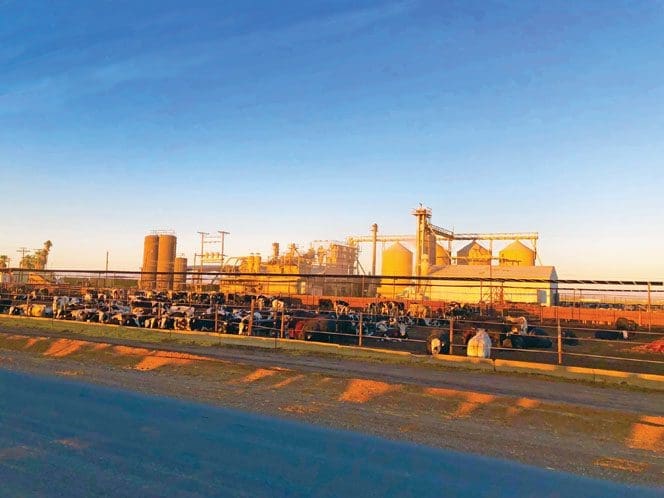

California’s Foster Feed Yard Sees Need for More Employee Training

By Larry Stalcup, Contributing Editor

Two to five years.

Jesse Larios figures that’s how long it may take to train a cowboy. No, not the “real” cowboy who grew up riding horses, working cattle and doing other farm or ranch chores. He’s referring to a pen rider, one who can sort feedyard cattle and eyeball a sick calf before it’s too late. He needs cowboys who don’t mind crazy hours, getting wet, cold, hot and dirty.

Larios is manager of Foster Feed Yard at Brawley, Calif., in the heart of the desert Imperial Valley. He is one the beef industry’s true ambassadors. No one promotes beef production more or loves it more. He’ll argue that cattle feeders and producers are the leading advocates of good animal welfare and concern for the environment. If there’s an issue that involves California or national cattle feeding or ranching, he’s right in the middle of it.

Larios virtually grew up at Foster Feed Yard, one of the nation’s first custom feeding operations. He learned from his father, himself a foreman at the yard for some 40 years, as well as the late Gary Foster, his brother, Rod, and their legendary cattle feeding father, Howard Foster.

“At Foster, we have two feedyards that provide us with a 36,000-head feeding capacity,” Larios says. “We also rent some space from other yards and currently are feeding about 41,000. Most are Holsteins that are on feed about 365 days.”

He sees an overall changing of the guard in California cattle feeding. “The next generation of cattle feeding is emerging, and that’s very exciting,” Larios says. “Younger family members are highly involved in management as their fathers or other relatives approach retirement or pass away.

“But at the same time, our experienced labor force is aging. People who have been here 20 to 30 years at all facets of feedyard employment are retiring. These loyal members of the area feedyard workforce are hard to replace.

“We’re finding that the next generation workforce is more urban. They tend to not want to work as many hours or work weekends or holidays. For those reasons, employees are hard to find. And when we do find good employees of this generation, we have to coach them along.”

Larios’ cowboy example highlights the situation facing feedyards in more places than just California. There are many jobs that pay as well or more and offer a more comfortable workplace.

“It’s tough to find cowboys,” he explains. “An ‘old’ cowboy can spot an animal getting sick before the calf knows it is sick. Now, it’s very had to find someone like that.

“We may need to develop the next cowboy crew, hopefully from people with a rural upbringing. We want cowboys with the attitude that ‘we don’t eat until after our cattle eat.’ We can teach them, but it may take two to five years.”

Youth groups like FFA and 4-H have been the roots for many leaders on agriculture. Larios sees them as logical places to find future feedyard employees.

“We have always worked with youth groups. My family is deeply involved in showing animals,” Larios says. “These young people are dedicated to what they do.

“Our next great set of cowboys and even feedyard management may be at FFA and junior colleges.”

More time is devoted to training. “With some new employees, we can’t take their general knowledge for horses or cattle for granted,” he says. “Pharmaceutical companies have always worked with us to provide training as a reminder of how to use animal health products. Now, we must provide full training for the labor force. It’s a different era for feedyard employees.”

$22.50 for minimum wage overtime – seriously?

Don’t expect the need for more employees to go away. California remains a major beef state. It has more than 500,000 beef cattle and is the fifth-largest cattle feeding state in the nation.

Now, a new wrinkle is being thrown at feedyards and other California ag producers. Starting in 2019, the State of California is raising its minimum wage to $15 per hour. Anything more than 40 hours is time and a half for overtime. “Since typical feedyard employees may work a 60-hour week, that puts time and a half at $22.50 per hour,” Jesse says.

“That puts us in a very bad spot. It will cost us a lot more to get the work done. My cowboys make $4 per hour over the minimum wage, so will the added time and a half apply to that also?”

Once again, people in the capital of Sacramento don’t realize that the Imperial Valley is not the Silicon Valley when it comes to a normal workday. Nine-to-five may work at Google or Apple – but not at a feedyard, dairy or vegetable farm.

Larios is often asked about bringing in employees from Mexico, just a 10-minute drive south of Brawley. “Young people in Mexico favor the urban life like in the U.S. Agriculture needs workers, but when they cross the border they immediately go to the cities.”

And he contends that Mexicans and other foreign people should come here legally. “As a legal immigrant myself, we need to approach it in the legal way. Legal is the right way to do it.”

So as the low availability of good employees and the required reduced work week put even more pressure on California feedyards, Larios and the new guard of feedyard operators will continue to find ways to maintain their reputation as some of the best fed-cattle producers in the nation.

As Larios says, “We will continue to need good employees, even if it takes two to five years to train them.”