By Patti Wilson, Contributing Editor

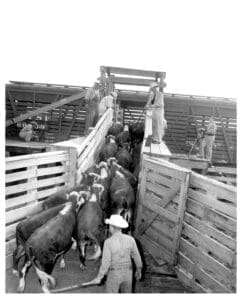

Railroad transit of livestock endured until the end of World War II. It faded away with the improvement of roads and development of the trucking industry.

It’s a safe bet we don’t spend much time pondering the origins of livestock transport. When it comes to shipping cattle, we are more concerned with the trucks showing up on time. It turns out, however, that there’s a winding history behind putting the proverbial wheels under livestock.

Ancient History

In ancient times, livestock were transported among archipelagos (large groups of small islands in a local body of water) by boat. Granted, they were small vessels and probably paddled by hand. There is an archipelago of great size in the Baltic Sea off the coast of Finland. Looking at it on a map, one could understand why that would work. And one would assume the livestock were small.

Written Records

The first written record of livestock transport by ship was in 1607. A vessel by the name of Susan Constant was transporting emigrants from England to Jamestown, one of the first settlements on our continent. As the New World colonies developed, supply ships from England carried livestock as regular cargo. Both Plymouth and Philadelphia benefited from purebred stock. In about 90 years, exports of cattle and packed meat were shipped regularly from the port of Philadelphia to the West Indies.

This sounds good but was not a pretty picture. Poor feed supplies, overcrowding and rough seas reportedly contributed to a 50 percent livestock death loss. Nevertheless, British colonial expansion marched west across the globe, causing continued growth of the livestock and meat trade.

The Aftermath of the Civil War and Transhumance

In the late 1800s, cattle ran wild in the greater Texas area; millions roamed free in the absence of southern ranchers, who left to fight for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

When the war ended, demand for beef in the highly populated North opened a great opportunity for cattlemen. Texas ranchers drove, depending on the source, up to 27 million head of Texas Longhorns north. The majority of packinghouses were located in the Chicago area. Later, cattle were driven to railheads in Kansas and shipped from there to the Windy City. Driving cattle is called transhumance movement. It is a French term meaning, literally, “across ground.” In many cases, it refers to the movement of livestock for grazing, although it is also employed to describe the movement of cattle to northern packinghouses and railheads in the latter 1800s.

This part of American history is highly storied and romanticized. Although it signaled an important watershed in the annals of beef, the cattle drive era of livestock movement was brief.

Railroad development increased dramatically, beginning in the 1850s. Chicago was a hub of activity. By 1860, more than 1,800 miles of track had been laid, extending in all directions from Chicago.

According to the Journal of Animal Science, “The first shipment of live cattle to Chicago by rail occurred on Sept. 5, 1867. Twenty carloads of Texas Longhorns left the railhead at Abilene, Kan. on the Kansas Pacific Railroad, destined for the Chicago Stockyards. This landmark event forever changed the face of the beef industry. Cattle from western and northwestern Texas were driven to railheads for transport to major feeders, processors and packers of the High Plains, Great Plains and Midwest.”

In a slightly different version of history, writer Bob Welch, in RanchingHeritage.com, says Joseph McCoy is responsible for the initiation of the Texas-to-Kansas cattle drives. McCoy negotiated cattle shipments from Abilene to Chicago via the Hannibal and Saint Joseph Railroad Company in 1867. “McCoy’s vision created the cowboy as an undying cultural myth unique to America, established the primacy of Chicago as a meatpacking center, spurred the boon of commerce to southern Kansas and resulted in the railroad as the means to make it all happen for the next century.”

As time passed, processers and packers multiplied. Expansion was driven by refrigeration technology. The refrigerated railcar was patented in 1868, and the need to trail cattle had disappeared by 1889.

The Santa Fe Railroad built more than 9,000 wooden stock cars between 1850 and 1900. By 1910, there were more than 78,000 cars in use across the industry.

Improving Conditions for Livestock

The transportation business came with a steep learning curve. Driving cattle by transhumance, the better drovers could report a 3 percent death loss. Loading them on railcars was a different story. Late 19th century rail systems posted an average of 6 percent to 15 percent loss. This figure became unreasonable to ranchers and the inevitable animal welfare advocates. Among their complaints were schedules that led to overcrowding, inhumane handling and deficient care in terms of feed, water and rest. In 1906, Congress enacted the “28 Hour Law,” setting a time limit that livestock could be on rail or ship transit without feed and water. Five hours rest was required for each 28 in transit. The law was originally written for rail transportation but was updated in 2006 to include trucks.

Trucks and Roads

In the early 20th century, rail transport dominated the beef industry. Trucking was in its infancy, and road construction had not begun in earnest.

Trucking was gaining a foothold, however. It was found to be more economical and gave greater flexibility to producers. As that segment of the industry grew, demand for better infrastructure helped create an interconnected road and rail distribution system throughout our country. The livestock sector pursued Congress to expand and improve roadway systems. By the end of World War II, railcar transit had all but ended; roadway systems were being updated, transitioning away from pedestrian, horse-drawn or driven stock traffic to motorized vehicles.

Engines that could move heavy loads were evolving quickly. One of the last and greatest improvements was the construction of Dwight Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System. The connection of major U.S. cities was well underway, putting a final nail in the coffin of the livestock railcar.

Modern Issues

Nearly all livestock have been hauled by truck since the 1970s. Decreased time in transit and improved cattle-handling practices have greatly lessened death loss enroute. The industry has turned its attention to the complex issue of “transport stress,” using modern scientific methods to research animal behavior and environmental factors that contribute to morbidity and death. According to the Journal of Animal Science, shipping is still considered one of the most stressful events that cattle will experience in their lifetime. In the U.S., factors that “produce an observable negative economic impact have been the primary focus of transport research.” These include disease, mortality, injury and carcass quality.

Considerations being studied are pre-transport management, noise, vibration, novelty, social regrouping, crowding, temperature and humidity, feed and water deprivation, loading, unloading and time in transit. There are more. This is not a simple task from a scientific standpoint, either. It is nearly impossible to design a study to identify the contribution of all factors. Scientists forge onward, however.

What’s the next step in livestock transportation? Only our imaginations can come up with an answer. Until then, happy hauling!

Innovations to Improve Transport

Technology is fast catching up to the needs of livestock transportation. AgriTechTomorrow.com provides seven innovations currently being evaluated that are designed to improve livestock well-being during transport. They include:

- Real-Time Monitoring Systems – Sensors can collect data from inside livestock trailers and transmit it wirelessly to provide insight into changing conditions, including temperature and humidity.

- loT Technologies Supported Trailer Disinfection – Makes cleaning more precise, specifically “baking” (167 degrees for 15 minutes) to kill pathogens.

- Hydraulic Lift Decks – Most useful for hogs and small livestock.

- Air Filtration Technology – Continuously monitors air quality and alerts users when they need to change filters.

- AI Route Optimization – AI algorithms can analyze various factors such as real-time developments like traffic and weather to find the best possible routes.

- Telematics – Livestock businesses can use tracking technologies to monitor driver behavior.

- AI Health Analytics – Understanding high-risk conditions of certain livestock that should never be transported and recognizing others with unique transport requirements.