By Larry Stalcup Contributing Editor

Even with low grain prices, another huge corn crop in the bin and record cattle markets, feedyards are still tweaking rations to generate the highest gains as efficiently as possible. Finding and delivering the right feed formula requires continuity between yard managers, nutritionists, mill operators and other yard personnel.

While feedyards generally have a common goal of finishing cattle after they leave the ranch, small-grains pasture or backgrounding operation, their feed preparation and specific rations often differ. That’s usually true regardless of whether they’re a northern state feedyard, one in the Southern Plains, or even yards only a few miles apart, says Jason Smith, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension beef cattle specialist in Amarillo.

“Feedyards continuously work with consulting nutritionists to develop and deliver what they believe to be the optimum or best-cost rations and feeding strategies for a specific yard,” Smith says. “Yards will often try to capture additional value by feeding one ingredient instead of another. They will regularly adjust rations to account for differences in ingredient composition, availability and financial opportunity.”

Low corn prices are again forecast for 2026. But that, and price of other grains, can change. “There have been periodic shifts from corn to wheat or milo for some yards,” Smith says. “The challenge is whether the alternate grain can be purchased cheaply enough and in a large enough volume to justify the change. That may be only a month’s supply for some feedyards, or the entire year’s supply for others.”

Ration Roughages

Receiving rations can be tricky when dealing with roughages. “From a logistical standpoint, roughages are challenging for some feedyards and feed mills.” Smith says, noting that’s one reason many yards have adopted the use of a complete starter feed such as Cargill’s RAMP.

In many cases, a two-ration blending system is used to transition feeder calves to a finishing ration. “That’s often preferred to help reduce the number of rations at the yard, as well as minimize the transition time from a receiving to finishing ration, particularly for heavy yearlings,” Smith says. “The transition for beef-dairy calves can often be similar.

“Since a large portion of beef-dairy composites are raised at a calf ranch, they often arrive at the feedyard with considerable experience eating a blended ration. As a result, feedyards often have the opportunity to start beef-dairy calves similarly to how they would start native beef calves received from a grow yard or backgrounder.”

The beef-dairy calves initially receive a greater amount of mixed ration than calves that are not bunk broke. They could possibly skip a portion of a conventional receiving program that’s used to start calves or yearlings coming off grass. Those calves normally have been exposed to eating a mixed ration from a feed bunk.

It’s an Art

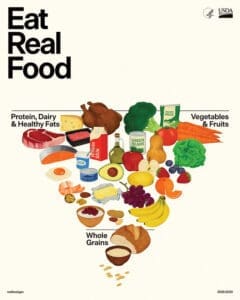

Typical rations are comprised of (on a dry matter basis):

- 55 to 65 percent corn or another cereal grain

- 20 to 30 percent byproducts, commonly either wet distiller’s grains or wet corn gluten feed

- 6 to 15 percent is dry roughage

- 3 to 5 percent being minerals, vitamins and additives

However, Smith says the “art and science” of developing rations continues to evolve over time.

Due to the value of the byproducts, quality control has improved for the production of the corn milling byproducts. “This has reduced nutrient variability, except for the onset of extraction of part of the oil from distiller’s grains, which at times has resulted in reduced energy content,” Smith states.

Nutritionists also have a better understanding of how to assign values to different ingredients, including roughage sources. “As a result, we can better optimize roughage inclusion level, depending upon feed mill constraints, ration-blending efficacy and level of feed-bunk management,” Smith says. “This can help minimize the amount of roughage required to be fed to maintain rumen health and minimize the risk of adverse digestive issues.”

He notes that this could differ if a farmer-feeder or other yard is feeding their home-raised roughages as a means of adding value to the silage or other crop.

Many cattle are being fed for longer periods to add pounds, which helps offset the shortage of feeder cattle. “As a result, some cattle may be on a ‘growing-type’ diet, or a particular stage of the transition program for an extended period before being stepped up to the final finishing ration,” Smith says. “The thought here is that cattle may have a maximum number of days they can spend on a final finishing ration before the risk of mortality or other issues late in the feeding period goes up.”

Some yards, while not necessarily changing the ration, have recently changed how they implant, “and more specifically, how they re-implant cattle throughout the finishing phase,” Smith says. “This has had the greatest impact on long-day cattle.”

In this approach, some yards are using an implant-plus-reimplant program. This program covers cattle either for the duration of their time in the feedyard, or is administered at a delayed time to ensure cattle are covered at the optimum times and improve return on the implant investment. Others may use a delayed, long-duration, single-implant program.

Micro-Ingredients

Smith points out other changes in ration development, including different uses of micro-ingredients. “There is more strategic timing of ingredient dosing, particularly for some micro-ingredients,” he says. “More products are available that can be delivered or ‘dosed’ through the micro-machine, which increases flexibility at the yard.”

Higher levels of zinc are being fed, as is a higher level of vitamin E to high-risk calves during the receiving phase. There is less overfeeding of fat-soluble vitamins A and D due to cost and greater supply chain issues, Smith says, adding that feeders have adjusted sources and levels of added fat over recent years in response to supply issues and competition from other industries.

He says some manufacturers have added value to other ingredients, such as Cargill’s Sweet Bran Plus wet corn gluten feed that often contains added micro-ingredients. “This potentially reduces the number of ingredients that the mill operation needs to handle, which helps to minimize the time and cost associated with batching feed,” he concludes.

“Some feeders will feed multiple corn-milling byproducts as a means of reducing dietary starch level and ensuring access to one if short-term availability of the other becomes an issue. But this often results in feeding far more protein than is necessary.”