By Codi Vallery-Mills, The Cattle Business Weekly

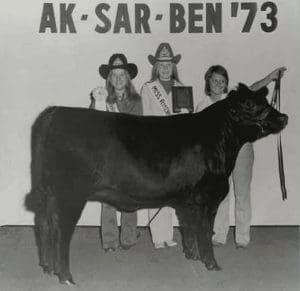

No one was more surprised that Patti Wilson was named 1975’s Nebraska Angus Queen than Patti Wilson herself. She states it was an honor that “caused me great discomfort because I am not a queenly person at all.” But the selection committee likely saw something in Patti that day that she was yet to discover in herself – unexpected talent.

Decades later, Wilson now reflects back on those hidden talents and how she has used them to gain success in the agricultural industry.

In 1976, she would be on the Univer- sity of Nebraska Livestock Judging team that won the American Royal and the carload judging at the National Western Livestock Show. She was the only girl on the team. Wilson says it was the hardest and best thing she has ever done in her life. She says it had nothing to do with women’s rights at the time but more to do with expectations of family and judging coaches.

“In my family, I was expected to go to the university and be on the judging team. It didn’t matter if I was a girl or not. But it was expensive to have

one girl on the team needing her own hotel room. I worked hard to justify the expense and I earned my spot. I wasn’t going to give my coach any excuse to leave me home,” Wilson says.

Later, her eye for livestock and quick- ness with numbers would land her a job with Kearney Livestock Market, procuring cattle and working the auction block as a scale master and clerk. Wilson says she never was uncomfortable in the traditional fieldman position and was received well by cattle producers.

A Path Unanticipated

In 2002, CALF News hired Wilson for ad sales and writing. It wasn’t a position she ever envisioned for herself, but Wilson took to the writing part of things immediately.

“I’ve been lucky to have this job. I am always in awe when I get to go to press conferences or industry events. For a short, little farm girl from Seward County it never gets old,” Wilson says.

Her writing spans hard news topics to feature articles like producer profiles, which are her favorite. Wilson enjoys hearing about how other people do things on their operations and how it might benefit the CALF News readership.“Interviewing good people, good cattle people is my favorite thing to do,” she says.

“I hope my articles take a subject to a level everyone can understand,” Wilson says.“I want to bring it to a level that would create interest in high school students for agriculture.”

Not all topics can be light-hearted though. Wilson says an article where she covered a ranch devastated by a Kansas wildfire back in 2019 is one of the most memorable stories she has written.“The lady survived by riding her horse into a green wheat field. They lost almost everything and that is one story I will never forget,” she says.

Through the past 20 years with the ag publication, Wilson has seen shifts within the cattle industry. She witnessed the consolidation of the vet health pharmaceutical companies; the vertical integration of packers and feedlots; progress of technology in livestock marketing and the advancement of and use of Continental cattle, which Wilson notes has pulled back in recent years but was very popular in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

“When continental cattle first came around in the ‘60s it was really exciting times. Some of us had never even seen a Charolais bull. So here we were with black cows having white calves. I mean holy cow. People were wanting to try a little bit of everything at that time and so we were buying different semen and breeding cows. All that color and differ- ent body types … today that wouldn’t go over at all but at the time it was some- thing to experience,” Wilson says.

Her Farm Family

Raised on a diversified farm in Seward County, Neb., Wilson grew up in 4-H, showing cattle and knowing that the livestock industry was where she belonged. She went to AI school as a teenager and received an animal science degree from the University of Nebraska.

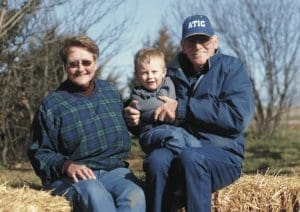

After college, she married Richard Wilson and moved to central Nebraska. The couple has been married for 45 years and has two grown daughters – Robyn Goddard of Prairie City, S.D., and Micky Burch of Seward, Neb. They have one grandson, Miles.

They raise commercial Angus cattle but are in the midst of transitioning their cowherd into a yearling operation because they need something that requires less labor as they get older.

The goal with the cattle herd through the years was simply to make a living and pay the mortgage off on the land. “And our land is debt-free today. It was an enormous thing to be able to do and the cattle did it. I have to give credit to my husband. He really worked hard on the marketing of the cattle and the financial end of things to make it happen.”

The only thing Wilson has on her bucket list is raising and showing Southdown sheep. She has a big heart for sheep and routinely shows at the Nebraska State Fair. For 11 years, Wilson has attended the Nebraska State Fair and has nine reserve champion rosettes for her efforts. The champion title remains elusive for Wilson, but she says they have “done pretty well for what our little, tiny flock is.”

Richard and Patti started out ranching from scratch, which is a thing everyone advises against, Patti says, and she wishes they wouldn’t.

“We did not inherit anything. We did this all on our own and it was tough. Our place here is what we built together, and it took our whole lives,” Wilson says.“We have repeatedly heard that you can’t do this unless you inherit or work with your folks. And that is just not true. It is hard, and it might require a job on the side, and it may take your whole life, but just be patient. It can be done.”

And that is a story worth writing.

This article first appeared in The Cattle Business Weekly. Reprinted with permission.