Beef Industry’s Maligned Carbon Footprint

By Larry Stalcup, Contributing Editor

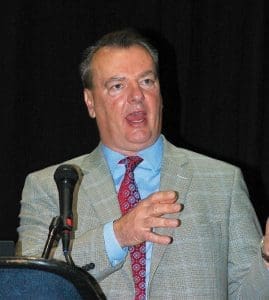

Frank Mitloehner is mad, sometimes fuming. If you spread manure about the beef industry’s carbon footprint, he’ll scoop up your mess with the facts. Blame greenhouse gases (GHG) on bovine, he’ll corral your Beyond Beef bias with the truth.

Mitloehner, a professor at the University of California at Davis, has become the anti-beef crowd’s nastiest nightmare. Twitter is his game and he has learned to master the social media means of communication.

After only a year and a half on Twitter, his tweets manage to make 3 million impressions a month. And his message hits environmentalists and food activists where it hurts.

He keynoted the International Livestock Congress in March during the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, a few days before the entire event was shut down early due to coronavirus fears. The congress brought together producers, animal health professionals, government officials, domestic and foreign ag students and other allied industries.

Mitloehner rebuffed two allegations spouted by “our friends [anti-beef activists],” as he called them – false claims that land used for livestock growth should be planted in food for people, and one in which cattle emit huge amounts of GHG.

“I decided for myself that enough is enough,” he said. “A month ago The New Yorker [magazine] reported that eating 4 pounds of beef has the same GHG impact as a transatlantic flight.

“Does anybody here believe that? When you put out stuff that is not factual, I will throw my scientific weight into the arena and rebuff it.”

Mitloehner contended that climate change is occurring, as it always has. “Some question whether human activity is driving the changing climate. Most scientists say it does,” he said, adding that agriculture has been deeply affected, through drought in some areas and too much rain in others.

Methane hot air

GHG, namely methane, CO2 and nitrous oxide, form a blanket over the Earth’s atmosphere to control global temperatures. CO2 has a lifespan of thousands of years. “But that’s not true for methane,” Mitloehner said, pointing out what animal activists raise a stink about. “It has a lifespan of 10 years. After 10 years, methane is destroyed. That is hugely important.”

He noted there are about 560 trillion grams of methane being produced by fossil fuel production and use, as well as biomass burning, landfills and waste and ag production. However, about 550 trillion grams of methane are destroyed by oxidation.

“If you had a ranch with 1,000 cattle that was established by your parents or grandparents 50 years ago, the first 10 years that ranch produced new methane for the atmosphere,” Mitloehner said. “But after the first 10 years, the amount of methane produced by those cattle and the amount destroyed in the atmosphere equaled each other. Over the last 40 years, that ranch did not add additional warming to the atmosphere.”

Plant- and cell-based food production leaders don’t tell that story, “they say animal agriculture needs to go bye-bye,” he said.

In addition, GHG from livestock is different from fossil fuel use. Mitloehner said when livestock graze on grass, they remove forage’s cellulose, the most abundant biomass in the world. “What can digest cellulose – ruminants?” Mitloehner said.

The cellulose is produced by carbon from CO2; the ruminant eats the grass that contains cellulous.

“Some of that carbon becomes methane, which is either belched out or derived from the manure the animal produces,” he said. “That methane is in the atmosphere for 10 years, after which it is destroyed.

“So the cow recycles the existing carbon over and over in a cyclical manner. If you have a constant number of livestock on a ranch, dairy or feedlot, you are not adding new carbon to the atmosphere.

“We have just been able to get this narrative out there [published in scientific journals]. We are now getting traction. Maybe pretty soon our ‘special friends’ will know that and will change their narrative from GHG to something else.”

While cattle are upcyclers, GHG generated from fossil fuel users remains in the atmosphere. Through carbon recycling, livestock production actually helps offset GHG produced from burners of fossil fuel. “Major customers of animal ag products need to make this a top topic in their objectives,” Mitloehner said.

Overall, only 3.9 percent of GHG is produced by animal agriculture in the United States. Only 2 percent comes from beef cattle from direct emission, according to the EPA. For the entire life cycle it is 3.3 percent for beef emissions. Worldwide, GHG is 6 percent for beef. Globally, all livestock have a GHG contribution of 14.5 percent.

“Of all the countries in the world, we have the lowest carbon footprint for livestock production,” Mitloehner said. “We produce 18 percent of all of the world’s beef with only 8 percent of the cattle. If there is one place in the world where we should produce beef it is right here. We know how to do it in an efficient way.”

He warned that anti-beef activists won’t stop attacking livestock production when the message on methane is spread.

“Mark my words, the Achilles heel, which is currently methane, will be replaced with something else in the near future because they will lose this battlefield. If it’s the last thing I do on this Earth, they will lose this battlefield.

Reduce waste

Alarmingly, close to 40 percent of all food is wasted. The highest amount comes from fruits and vegetables. That’s both in underdeveloped countries and developed countries. “That is not acceptable,” Mitloehner said.

To meet what is called the “2050 challenge” [when the population reaches 9 to 10 billion people, efficiency will be critical.] “We’re 7.6 billion now and will see 9.5 to 10 billion in 2050,” Mitloehner said. “We will have more people to feed but no more natural resources to do it. We have to become more efficient in how we produce food.”

He added that worldwide land used for agriculture is tiny and most of it is only suitable for grazing by ruminants. It cannot support crops, but can support cattle, which, again, upcycle the forage to produce high volumes of protein needed by consumers.

Unfortunately, too many consumers believe crop and livestock production should resemble that of the 1950s, when farms had just a few cows, pigs and chickens. However, larger more efficient production is needed to meet the demands of the growing population, Mitloehner explained.

He is fully dedicated in his mission, even though he teaches and conducts research at UC Davis, long considered one of the most left-leaning universities in the nation. Mitloehner laughed when he referred to it as the “People’s Republic of Davis.”

Nevertheless, he is persistent in educating others. He has taken steps to even hire journalists as well as researchers to get the facts out. He expects producers and feeders to do the same.

“It’s not just good enough to be good farmers, good food researchers,” he said. “If we don’t get the word out, it’s worth nothing. Science communicating is extremely important.”

For more on Mitloehner’s research, visit his UC Davis website at Clarity and Leadership for Environmental Awareness and Research Center, or CLEAR Center – https://clear.ucdavis.edu.