By Larry Stalcup, Contributing Editor

It’s inconceivable, but detecting foot and mouth disease (FMD) in even one bull, cow or calf could shut down the U.S. beef industry overnight. Industry studies show losses could push $200 billion.

Fortunately, the United States remains FMD-free, but FMD lives in two-thirds of the world. Consequently, animal health and many beef production leaders contend that feedyards and other cattle operations should have a plan to shield themselves from an infected animal – or human – FMD carrier and prevent the catastrophic disease from spreading.

One unchecked FMD outbreak could destroy domestic and foreign markets for U.S. beef. Any profit for calves, feeders or fats could falter. To help educate feedyards and other cattlemen about guarding against such a disastrous threat, a Secure Beef Supply Plan exercise was conducted recently at the 75,000-head-capacity XIT Feeders in Dalhart, Texas.

Texas Cattle Feeders Association (TCFA) presented the program in cooperation with Gene Lowery, XIT Feeders general manager, its parent company Five Rivers Cattle Feeding, and state, regional and national animal health agencies. Regional university veterinary schools and Extension personnel also lent a hand.

TCFA President and CEO Ben Weinheimer told exercise participants the Secure Beef Supply (SBS) Plan is designed to provide the industry with continuity of business if FMD is discovered in the United States. He said even though feedyards and other cattle operations are not required to have an SBS plan, a plan is still needed for increased biosecurity.

During an FMD outbreak, an SBS plan would benefit producers, feeders, haulers and packers. SBS is designed to help cattle operations with no evidence of infection to limit exposure of their animals through enhanced biosecurity. The plan would help them move animals to processing or other premises under a movement permit issued by regulatory officials.

Weinheimer said other biosecurity plans have evolved over the past 20 years after FMD was confirmed in the United Kingdom in 2001. UK cattle and sheep producers were forced to euthanize millions of animals. Shortly afterward, TCFA, USDA, the Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), the Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) and other agencies held biosecurity exercises in Amarillo, Texas and elsewhere.

“Initial exercises were hosted in 2003; a tabletop exercise was hosted in 2007 and again in 2016,” Weinheimer said. “After the exercises, state and federal animal health agencies enhanced their biosecurity planning, but we kept coming back to the need for cattle feeders to step up our efforts in creating our own plans and procedures to implement.

“Since then, feedyards have worked with a number of agencies to create individualized plans for their feedyards, so that if and when they need to be implemented, we have the ability to switch from normal operations to heightened biosecurity.”

TCFA has worked with XIT Feeders and other member feedyards to develop SBS plans. Veterinarians play a key part in developing a plan. For a feedyard, large or small, the process starts with naming a biosecurity manager. He or she is responsible for developing the biosecurity plan with the assistance of a veterinarian.

The Line of Separation

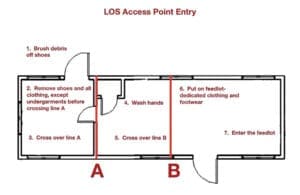

The SBS plan’s first line of security is the Line of Separation (LOS). The LOS establishes various biosecurity boundaries. The LOS boundary could be established by fencing, large hay bales, or if for an extended period, even drywall, plywood or other material.

The LOS would be marked by signage. Signs would designate access points for people, animals and vehicle entry and exit, designated parking areas and cleaning and disinfectant (C&D) stations. Signs would also identify pathways for transport of feed and other ration ingredients, manure management, carcass movement and disposable stations and other biosecurity measures.

Five Rivers’ Dr. Josh Szasz, DVM, provides oversight and direction for the company’s feedyard SBS plans. Pate Chavez, XIT Feeders assistant general manager, helps lead that yard’s plan. “We created the plan several years ago and are pleased to implement it in this exercise to measure biosecurity,” Chavez said.

“The LOS can be complex, but try and make it simple,” he noted. “Try to limit the LOS access to one point. That will increase the execution efficiency.”

Szasz said employee dedication is critical. In the XIT Feeders plan, all employees enter the feedyard at a single location. They park in the same designated area. Additional employees may be needed if the plan is implemented. Under enhanced contamination security, the plan would even require employees to change clothing when they get to work and at quitting time.

“We would have to keep employee feedyard clothing here,” Chavez pointed out. “That means there will be a laundry set up to wash the clothing.

Remember, the plan is implemented only in the event of an FMD or other foreign animal disease emergency. Chavez and Szasz reviewed these details and other practices needed in XIT Feeder’s SBS plan:

- XIT Feeders has about 50 employees. Department heads would train those under their leadership, with emphasis on how operations would change if the plan was enacted. Employees must park vehicles in a single area outside the LOS. After brushing debris from boots or shoes, they would enter through a single entry point, and remove shoes and clothing other than undergarments before entering a separate room to wash their hands. In a third room, they would dress in feedyard-dedicated clothing and footwear before entering the feedyard. Upon completing their workday, employees would follow the opposite procedure by changing out of their work clothes, washing their hands or showering if needed, and then changing back to their street clothing. To ease employee traffic and confusion, they might be asked to arrive and leave on staggered schedules.

- All vehicles and equipment not carrying livestock must be C&D prior to crossing the LOS, focusing primarily on the lower half of the vehicle. Trucks hauling livestock may not cross the LOS. While XIT Feeders normally has two shipping facilities, it would switch to one shipping area. Since that would require moving cattle from across the feedyard, cattle from more distant pens would likely be moved first. Outside vendor and contractor vehicles must also go through the C&D station. Vendor drop-offs would be in one location.

- Loading and unloading animals, while normally done by truck drivers, must be handled by feedyard employees. This and other assignments would involve more employee cross-training.

- Animal movement may differ in an FMD emergency shutdown. Cattle in transit would likely be accepted, but require quarantine. The length of time involved would force changes in cattle movement.

- Carcass disposal would be another challenge. Rendering trucks cannot cross the LOS. There is no designated manner of removing dead animals, but if chains or other materials are used to retrieve carcasses, they must be C&D before and after the movement. Composting of dead animals may be needed to eliminate cross-contamination.

- Feed and commodities must be delivered by covered transport. For the 75,000-head feedyard, that would typically involve 18 or more semi-loads of corn per day, along with trucks hauling hay, Sweet Bran, RAMP or other feed supplements. All trucks would be C&D before leaving. Additional feedyard employees may be needed to make sure single piles are made in hay and feed supplements. After corn is dumped in the mill pit, pit gating would be disinfected.

- Feedyard personnel would outline the procedures to trucking companies, independent haulers and feed companies. Vendors would also be advised of what is required of their truck drivers and others in an FMD emergency.

- Silage harvest will present obstacles. As with other outside trucks, those delivering silage would go through C&D, dump their load and C&D out. In XIT Feeder’s case, that would be about 300 trucks – per day – over a two- to three-week period during silage harvest. A portable scale would be used to weigh trucks in and out. Traffic from other trucks would require more careful delivery planning.

- Manure management would require feedyard employees to clean pens, a task normally performed by outside manure handlers. The feedyard has storage space to hold manure scraped from pens for about two years. More space could be added. Since the manure is typically sold to regional farms for fertilizer, trucks hauling manure would be C&D.

- Rodents and wildlife may require extra deterrence in an FMD emergency. Feed spills must be cleaned ASAP to help prevent rodents or other wildlife from eating spilled feed and possibly spreading FMD elsewhere. All trash would be collected daily and placed in dumpsters. When dumpsters are full, waste management trucks would go through C&D going in and out.

SBS Plans Will Differ

Five Rivers hosted a similar mock biosecurity preparedness event at its Kuner Feedlot in Colorado in late 2023. Five Rivers feedyard representatives, along with state and national animal health agencies, Extension personnel and others attended.

As with that exercise, the event at XIT Feeders reemphasized there’s no way of knowing if and when an FMD or other foreign animal disease outbreak would happen. If it did, the outbreak’s degree of infection, location and number of cattle involved could vary widely from one cattle-producing region to another.

An SBS plan for a large feedyard like XIT Feeders would differ greatly from a smaller 15,000-head feedyard or a farmer-feeder operation with a few thousand cattle or fewer. Still, a sound plan is advised and should be established before a disaster happens, Weinheimer said.

More Traceability

Szasz emphasized the need for transparency in the event of an FMD or other foreign animal disease outbreak. “If that happened, cattle transparency would be the difference between isolating an infected animal or herd in a matter of hours vs. days or weeks,” he stressed. “But if there’s one weakness in our production system nationally it is traceability. We need more EID usage and tracking capabilities.

“The better we get at that, the more likely we can maintain business continuity in regions where FMD has not been identified through a traceback.”

Szasz advised feedyard operators, backgrounders and producers to contact their regional or state animal health agencies to learn more about their local needs in establishing an SBS plan.

Information on developing an SBS plan is available at Securebeef.org. The site contains a self-assessment checklist for SBS readiness. It provides charts, graphs, photos and videos of SBS guidelines. State animal health agencies feature information for their state cattle and other livestock operations.

The Texas Animal Health Commission site is tahc.texas.gov. It offers access to no-cost radio frequency (RFID) tags and information on more advanced transparency programs.

As for XIT Feeders and other Five Rivers feedyards, most incoming cattle are easily traceable through EID and other tags. But if the unthinkable happens, these operations and others must be ready.

“We spent a lot of time developing our SBS plan,” Lowery said. “The exercise enacted the plan and helped all of our employees be better prepared for an outbreak. It was a confidence builder. If it happens, we can handle it.”

POROUS BORDER THREATENS TEXAS,

NATIONAL LIVESTOCK BIOSECURITY

With a potentially porous 1,237-mile border with Mexico, migrants who cross the Rio Grande River into Texas could accidentally carry FMD or other foreign animal diseases to ranches, farms or even feedyards, warned Dr. T.R. Lansford, DVM, deputy executive director of the Texas Animal Health Commission.

Speaking at the TCFA, XIT Feeders biosecurity exercise, Lansford added that the potential for FMD contamination is increased due to nine Texas seaports, 20 land ports, four international airports – and Texas borders five states.

“Two million or more cattle and millions of tons of products come through these areas annually,” he said. “Not just four-legged, but two-legged [beings] can be carrying viruses accidentally. A porous border does not lend itself to good biosecurity.”

Lansford noted how rapidly an infected animal can contaminate thousands of cattle. He referred to a map provided by North Carolina State University. Alarmingly, the map illustrated how a North Carolina animal that was accidentally or purposely infected with FMD through an act of terrorism could lead to cattle contamination in 27 states in a mere eight days.

In such a case, USDA will issue a 72-hour National Movement Standstill for the detection of FMD in domestic cattle and their germplasm, other cloven-hoofed animals and/or feral susceptible animals. Feedyards would need to execute their SBS plan immediately.

“That’s why it’s important to have SBS plans in place,” Lansford said. “The faster we can deal with this problem, the less the impact. It will be critical to get biosecurity in place so the movement of cattle can continue and to protect yourself if you [your cattle] are not infected.”