By Larry Stalcup Contributing Editor

The largest wildfire in Texas history stole much of the lifeblood of hundreds of ranchers in the northeastern Panhandle in late February and early March. Quick to catch national attention, the roaring, ruthless infernos killed 15,000 or more cattle and burned more than 1.2 million acres of grassland, according to state officials. Three people, including a volunteer firefighter, lost their lives.

But never believe that people in Panhandle towns like Canadian, Fritch, Borger or Miami will surrender to Mother Nature. With an outpouring of generosity that continues to provide hundreds of truckloads of hay and supplemental feed, reams of barbed wire and other fencing, clothing, food and enough water to fill a swimming pool, cattlemen and women and their neighbors in town are getting back in the saddle.

The Texas Panhandle and western Oklahoma are no stranger to fire. Drought never seems to let up. Some moisture had blessed the region this winter, but stretches of dry conditions and those West Texas winds finally created conditions ripe for the disaster.

The fires started on Feb. 26 during low humidity and winds gusting past 40 mph or more in Hemphill, Roberts, Hutchinson, Moore and Gray counties. A downed power line is believed to have ignited the fire in Hemphill County near Canadian. Within a day, the fires had burned 500,000 acres and surpassed 1.2 million acres by Feb. 29.

The Texas A&M Forest Service said it responded to dozens of wildfires burning more than 1.25 million acres from Feb. 25 to Feb. 29. Along with the Smokehouse Creek Fire that singed Hemphill, Roberts, Moore and Hutchinson counties, the forest service targeted three additional active wildfires in the Panhandle, including the Windy Deuce Fire in Hutchinson and Moore counties. It had surged through 142,000 acres.

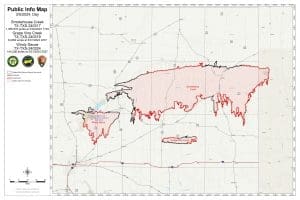

The magnitude of the Smokehouse Creek Fire was astonishing (see map). It stretched about 100 miles from east to west and 30 miles from north to south, an area bigger than at least one New England state. It’s estimated that from 400 to 500 structures were destroyed, including many homes and barns. One woman died as flames smothered her home in Borger. Another woman died when her car was surrounded by smoke and fire near Canadian. Fritch Fire Chief Zeb Smith died while fighting fire on March 5.

A mountain of manpower was moved into the fire zone. The forest service reported that hundreds of personnel and dozens of engines worked the fire areas. Hundreds of regional paid and volunteer firefighters were also engaged in the areas of rugged terrain that includes many canyons and gulches. Those areas were dotted with timber that continued to hold heat. Hot spots were everywhere.

Planes applied both dry fire retardants and water from nearby Lake Meredith. The U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management were also called into action to help contain and extinguish the smoldering prairie. Texas municipal and volunteer firefighters from as far as 700 miles away joined their Panhandle brethren in battling the ferocious flames. Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado and New Mexico firefighters also helped.

News of the wildfires and how to donate to help victims has spread worldwide. From The Guardian in the United Kingdom, the New York Times and about every major news outlet, to small-town dailies and weeklies and broadcast stations, the struggles of the fire victims continue to receive much publicity. Many stories centered on the fact that a power line from an electrical utility, Xcel Energy, ignited the fire.

Xcel issued a statement acknowledging that equipment from its subsidiary Southwestern Public Service Co. ignited the fire, but denied negligence alleged in lawsuits that the equipment was faulty. Southwestern Public Service is deeply rooted in the Panhandle, with employees located throughout the region.

Staggering Cattle Losses

Roberts County is one of the least populated counties in the nation. Fewer than 900 people live in its just over 900 square miles. A Roberts County Disaster Relief notice indicated the Smokehouse Creek Fire engulfed most of that land. Some 90 percent of the county was burned, amounting to about 436,000 acres.

The county estimates that 7,500 cattle were lost. About 25,000 more cows were without grass, feed and hay. About 90 producers were impacted, and the economic loss is estimated at $60 million in grass alone. With today’s high cattle prices, there are tens of millions more in cattle losses.

In Hemphill County, which neighbors Roberts to the east, AgriLife Extension Agent Andy Holloway estimated that from 6,000 to 8,000 mother cows died in the fire. He said many more might need to be euthanized due to burned hoofs and other injuries.

“We lost about one-third of our mother cows in Hemphill County,” Holloway said. “And there are still 15,000 cows that need hay, water and cake.”

From Hay to Hostess Snacks, the Highest Spirit of Giving

When the wildfires erupted, word spread fast on social media. Several Facebook pages have seen hundreds get involved. From Wyoming and across the Great Plains, to states bordering Texas, to producers and hay/feed merchants from the Rio Grande Valley on up, truckers have hauled load by load. Some have likely been on the receiving end during fire, hurricane, blizzard or flood conditions that struck their operations at some point.

Members of trucker communities supported them and their makeshift supply chains. Many more are making the Panhandle trips on their own dime.

“We’ve had 700 loads of hay delivered in Hemphill County,” Holloway said during a March 5 emergency producer meeting in Canadian.

Holloway is working closely with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Disaster Assessment and Recovery (DAR) program. DAR set up supply points for the delivery of hay, cubes and other feed, along with fencing and other materials to benefit ranch and farm communities in the paths of fires.

“The AgriLife system’s disaster recovery unit is trained to respond to wildfires, hurricanes, floods, tornadoes and other disasters,” said Blair Fannin, AgriLife DAR public information officer. “We set up three supply points in Canadian, Borger and Pampa, and a satellite point in Miami.”

“The outpouring of people sending feed, hay, fencing and other resources has been incredible. Thanks to everyone across Texas and other states for their help. It’s heartwarming to know there are so many who always help out farmers and ranchers in situations like this.”

“We have a system to directly ship hay right to your ranch,” Holloway told fire victims. “Gov. [Greg] Abbott was here today. He asked what do we need. I told him more hay and feed.”

Roberts County Extension Agent Hanna Sell added that the county has more satellite hay and feed points.

“My priority is our ranchers,” said Sell, who assumed the AgriLife agent post on Feb. 1. She was baptized into her job by the fire. “Remember, this is the Panhandle and this is Texas. People are trying to help us.”

Volunteer Fire Department Heroes

The mammoth wildfires were a challenge to all firefighters; especially those who volunteer in their local community volunteer fire departments (VFD). And it didn’t take long for overwhelmed VFD equipment to require repairs. Unfortunately, some VFDs didn’t have the finances to pay for a new transmission, engine repairs or even tires.

Among the outside sources that helped VFDs get their equipment ready for the next wildfire was the 100 Club of the Texas Panhandle. Headquartered in Amarillo, it serves the Panhandle’s top 26 counties. The 100 Club’s mission is to provide financial benefits to families of first responders killed or injured in the line of duty (see page 36, CALF News December 2023/January 2024 issue). But the club also provides funds to repair or upgrade equipment.

With the wildfire emergency, the 100 Club provided more than $300,00 to VFDs in nearly 10 Panhandle towns through March 8. (Editor’s Note: The author of this article serves on the 100 Club board of directors and was privileged to help deliver several checks to VFD members, grateful for the generosity made possible by 100 Club members and private donations.)

Sadly, the 100 Club also provided the family of deceased Fritch Fire Chief Zeb Smith with a financial benefit following his death while fighting the fire. Several other VFD firefighters also received compensation for injuries they sustained in the war against the wildfire.

How to Help

Help from the 100 Club coincided with the enormous outpouring of physical and financial assistance paid to the wildfire victims. There are countless ways to provide support to wildfire victims. Schoolchildren have used unique techniques. One volleyball team loaded their team bus with food, water and other goods for shipment to the Panhandle. Others have discussed making spring and summer mission trips to help ranchers rebuild fences.

Here are additional links to help donate:

- texaspanhandle100club.org

- texasfarmbureau.org/panhandle-wildfire-relief-fund/

- texasagriculture.gov/Home/Production-Agriculture/Disaster-Assistance/STAR-Fund

- tscra.org/disaster-relief-fund/

- TCFA.org

- oklahomacattlemensfoundation.com/giving

Facebook disaster groups and pages have been established. They include:

- Texas Wildfire Updates & Resources

- 2024 Panhandle fire assistance page

- Texas Tech University School of Veterinary Medicine.

After more than two weeks of fighting the wildfires a brief light rain, the blazes were declared 100% contained the weekend of March 16-17. However, donations continued to pour in from far and wide. Holloway told regional ranchers still weary from the events, “Make sure you use the supplies people have brought here. Some may say ‘give it to my neighbor.’ But we’re all neighbors. If you don’t take it, you have denied the people who gave it a blessing they made to you.”

USDA LIVESTOCK INDEMNITY PROGRAM, EQIP, OTHER DISASTER RELIEF

Financial relief is potentially available from the USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) and Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to help offset losses suffered from the massive Panhandle area wildfires.

The FSA Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP) aids with livestock losses due to disasters, including wildfires. LIP payments for contract producers would be based on 75 percent of the average income loss sustained by producers from cattle deaths. USDA’s 2024 payment rates are expected in late March, says Tiffany Lashmet, Texas A&M AgriLife agricultural law specialist in Amarillo.

She emphasizes that producers need to contact their local FSA office to determine exactly what is needed to file for a LIP or other loss claim.

“LIP provides indemnity payments for livestock killed in fires, for livestock that had to be euthanized as a direct result of the fires and for livestock injured by the wildfire that are sold within 30 days for a reduced rate,” she says.

“Producers will need to provide records of their losses that may include inventories, financial records, photographs, rendering receipts and veterinary certifications.”

The deadline to provide notice of loss and a payment application is 60 days after the calendar year in which the loss occurred, which would be March 1, 2025. However, Lashmet encouraged producers to file for LIP payments soon.

“Although the deadline is 60 days after the end of the calendar year, you don’t want to wait to get those documents together,” she warns.

Lots of Fixin’ Fences

Thousands of miles of fence were damaged or destroyed by the wildfires. The NRCS Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) may provide financial help for replacing fences.

“EQIP, while not disaster specific, could potentially be an option for producers seeking to implement certain conservation practices,” Lashmet says. “In some instances, building fences may qualify for EQIP funding.

Again, producers should work closely with their NRCS offices to make sure fencing programs meet specific guidelines for anchor posts, regular posts and other brace assemblies. Wire gage and wire attachments must also meet NRCS specs.

Forage Loss

Emergency grazing of CRP land is often implemented in situations like those involving wildfires. Producers should check with their FSA offices to determine if emergency CRP grazing is implemented for their location.

USDA’s Livestock Forage Program (LFP) could benefit producers who lost substantial grazing availability.

“LFP is not specifically wildfire related, but assists livestock producers who have suffered grazing losses due to drought during the normal grazing period,” Lashmet says. “Producers may qualify for LFP payments if a drought was declared in their area.”

The 2024 LFP payment rates will be released in April. The deadline to apply for LFP for 2024 losses is Jan. 30, 2025.

For more on state or national agricultural programs, contact your local or regional Extension, FSA or NRCS offices.

“We want to make sure producers and landowners are aware of what programs are available and what to ask about when they explore their options,” Lashmet says.