Straddling Both Sides of the Fence

By Walt Barnhart, Contributing Editor

Distrust among segments of the beef production chain has been common for more than a century.

This has led some in the industry to explore a different model.

Distrust among segments of the beef production chain has been common for more than a century. This has led some in the industry to explore a different model.

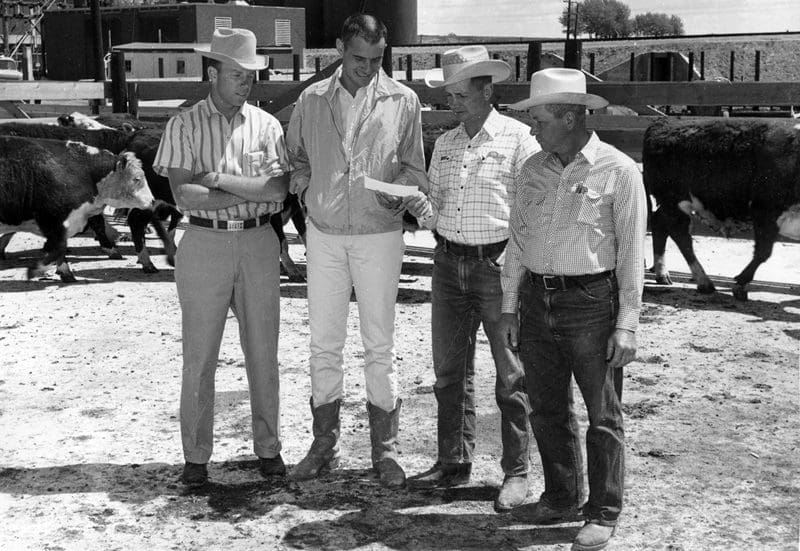

\Warren Monfort knew his own strengths. A dedicated cattle feeder beginning in the early 1930s, he worked hard to purchase high-quality feeder cattle, sort them properly and feed them a good diet, treating animals almost like show cattle. He was proud of the animals he fed.

His success was confirmed partly by rapid expansion. The capacity of his feedlot just north of Greeley, Colo., had increased to about 4,500 head by the time World War II ended; by the time his son Kenny joined the team in 1950, it had increased to 8,000. The lot’s size doubled to 16,000 head by 1955 and doubled again to 32,000 by 1960.

Accomplishments were also evident in the reputation he was gaining among those buying the cattle. The animals were widely recognized for their quality – even though they were not necessarily financially rewarded for it at the terminal markets in Chicago, Omaha and Kansas City.

No Love Lost

The Monforts thought packers paid too little for their animals, which obviously couldn’t be held for better markets. But this was only one of the reasons the Monforts hated packers. They also believed packers manipulated their own production to get the animals at the lowest price possible. Basically, they thought packers were merciless – and unscrupulous – when it came to how they treated their cattle suppliers.

At the time, packers would charge a yardage fee for animals purchased, whether those animals had spent any time in the yards or not. And the Monforts always thought shrinkage – the amount of weight cattle lost on the way to plants or terminal markets – was calculated higher than it actually was. It was costing about $6 per head to market animals through terminal markets, and feeders like the Monforts picked up a big chunk of that.

There were also limited marketing options. In the early 1900s, the beef-packing industry was controlled by what was known as the Big Five – Swift, Armour, Morris, Cudahy and Wilson. They slaughtered about 82 percent of the cattle and produced 95 percent of the fresh beef. They were pretty much the only game in town.

On the other side, packers thought feeders would raise animals for maximum weight gain and cared nothing for their quality and composition needs. They had razor-thin margins and, to keep their plants running, they would sometimes have to buy what they could get, regardless of cost or quality.

They thought they were being more than fair, though. In the 1950s Swift was boasting that more than 73 cents of the average beef sales dollar went back to pay for livestock and other agricultural products. Kenny Monfort was focused on the other 27 cents.

Looking for Options

In fact, Warren and Kenny were frustrated by the lack of options for their increasing supply of high quality fat cattle. It fell on Kenny to see if there were any companies willing to locate closer to their lots. It turns out there weren’t. The major packers thought it was better to ship the cattle than to try to find new employees and ship the meat long distances.

But Kenny came up with another solution. Capitol Pack in Denver was willing to operate a plant in Greeley if the Monforts would build it. Warren thought it was a terrible idea. They were cattle feeders, not packers, he insisted. The family should concentrate on what it did best.

Margins also supported feeding. Margins for packing plants were about 2 percent; feeding was in the 5 percent range.

Kenny thought getting into that side of the business made sense, though. In addition to financial benefits, the beef could age while it was in transit. They would also control how the beef went to market. And they could ride out the highs and lows of the cattle market.

His father eventually gave in. Construction of the plant started in the summer of 1959. Operations of Greeley-Capitol Pack began on May 16, 1960. The 92,000-square-foot plant cost $2 million to build and was able to process 600 cattle and 240 lambs per day.

It was a struggle from day one. After six months, Capitol Pack wanted out. Kenny wanted to keep going, using the Monfort name, but Warren was not convinced. Once again, Kenny prevailed. After the papers were signed, Warren looked at Kenny and with a smile told him, “At least I still have my teaching certificate. I don’t know what you’ll do.”

Warren managed the feedlots, Kenny the packing plant. Kenny jokingly said his father became just like other feeders. “He learned to hate me,” he said.

But he had been raised in the cattle feeding environment and knew they were feeder/packers, not packer/feeders. And he believed in the logic of what the company was trying to accomplish.

It was touch and go for the first year, with Warren and Kenny needing to go back to the bank with hat in hand to keep things afloat. They weren’t sure they would make payroll each week.

Monfort Packing Co., started making money in 1963, though, and was able to pay off its debt.

Competition and Labor

By this time, their competition was changing. The Big Five packers were getting out of the business. Iowa Beef Packers (IBP), which by 1969 had nine packing plants, had become the world’s largest beef producer – larger than its five largest competitors put together. And they were playing by their own set of rules.

IBP believed that not only was beef production antiquated, but the way people were paid for it was antiquated, too. The company focused on efficiency and productivity while lowering labor costs. That meant going up against the packing unions.

Those unions had been increasing in power since a 1935 government act that encouraged collective bargaining. In 1948, a strike by the United Packinghouse Workers of America led to a “follow the leader” model comparable to the automobile industry.

That was the system Monfort adopted when its plant became unionized in the early 1960s. They fell in line with the major packing companies, which Kenny thought was just fine.

In a 1969 newsletter to employees, Kenny spelled it out. “It seems so simple and maybe a little corny,” he wrote. “Good pay for good work. Everyone profits. Management is not interested in cheating a little on the pay, not interested in being ‘cute,’ not interested in contracts way under the national rate and not interested in the ‘hard line.’ Our employees are not interested in a slow down or in inferior work. This is a combination that has worked to everyone’s benefit.”

IBP took a different line. It had strikes that stopped operations for 28 months over a period of 13 years, with one particularly nasty strike causing one death, major injuries and destruction. By contrast, Monfort had one fairly calm, 56-day strike over wages in 1970.

But in 1979, labor costs for the Monfort Greeley plant were about $6 to $7 million higher than those in IBP plants. Kenny put his foot down during negotiations for a new contract in 1980. It might have signaled the beginning of the end. The company would close the plant later that year. It took a toll on Kenny’s outlook.

“That closing and the effects of it on our community in general, and our employees in particular, are marked down in my book as my greatest failure to date,” he would later write. “I had a number of failures in personal relationships, some political failures and those everyday types of goof-ups … But all of those type things pale in comparison to the problems that I could not solve involving our business and our plant in Greeley.”

In 1982, the company re-opened the Greeley plant, but without a union and at wage rates about half of what they had been before. The union filed a complaint that overturned a union election and getting compensation for its members.

While competing with the massive IBP was challenging, it became impossible when companies with really deep pockets got involved. IBP sold out to Occidental Petroleum while the next largest packer, EXCEL, was purchased by Cargill, which went on to buy the Spencer Beef Division of Land O’Lakes. Though Monfort fought the sale, its efforts failed. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, the company ended up selling its own business to Conagra in 1987.

A Different Approach

The Monforts brought a cowboy and cattle feeder attitude to the beef packing industry. They honored handshakes and offered fair wages. They paid immediately for fat cattle, in good markets and bad, with checks sellers knew would be good.

Furthermore, as Kenny had told a House Agriculture Subcommittee in 1966, thanks to the Monforts “other packers have been forced to modernize and improve both their facilities and their buying techniques.”

He believed that feeders or groups of feeders should also have the “freedom to improve their economic position by further processing their production.”

Just wanting a better market for their cattle, Warren and Kenny Monfort couldn’t have foreseen the eventual consequences of getting into the packing business. They made their mark, though, and probably took the industry in directions it might not have otherwise gone.

Walt Barnhart is the author of Kenny’s Shoes: A Walk Through the Storied Life of the Remarkable Kenneth W. Monfort. He can be reached at carnivorecomm@msn.com.