Ogallala Summit Confronts the Aquifer’s Adversities

By Larry Stalcup Contributing Editor

Their mission is to prime the pump of High Plains water conservation. And stakeholders in the celebrated Ogallala Aquifer are pooling their knowledge to enhance the threatened gargantuan groundwater source – one that supports nearly one-fifth of the nation’s wheat, corn, cotton and cattle production.

During the recent virtual Ogallala Summit, crop and livestock producers, agronomists, ag researchers, engineers and water policy developers were among many who Zoomed into the forum. It would have made irrigation pioneers proud.

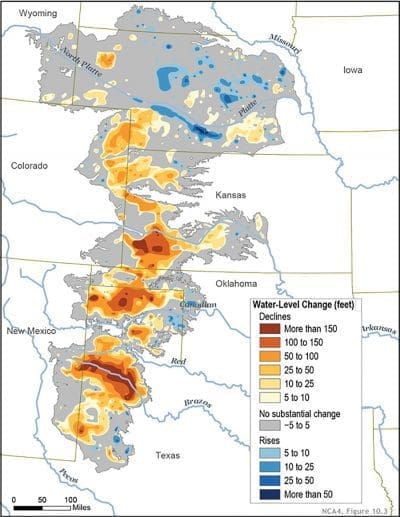

The 174,000-square-mile Ogallala is the lifeblood for much of High Plains’ agriculture. But after supplying irrigation to farms from South Dakota down to Texas since the 1950s and earlier, the aquifer has been shrinking for years. Decades of irrigation and failure of the Ogallala to recharge has forced the capping of hundreds of dried-up irrigation wells. Hundreds more struggle to provide enough supplemental water needed to produce anything close to trend-line or average yields.

In the southern High Plains, most irrigators have strived to improve water use efficiency. They saw water scarcity coming. For many, it has been through using low-energy precision application (LEPA), surge flow, subsurface drip or other water-saving measures. With better technology through precision ag, more efficient nozzling, smartphone apps to control watering systems remotely and other advancements, those improvements continue across Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Kansas, Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota and Wyoming.

The summit highlighted producers and others who are taking further voluntary conservation steps. Some use voluntary Water Conservation Areas (WCAs) to streamline water management and reduce withdrawals from the Ogallala. Others are enrolled in Master Irrigator programs. Additional programs aim at educating producers about better conservation techniques that improve efficiency. And there are more teaching efforts with 4-H, high school, college and other groups as targets.

Among innovative growers participating in the summit was Gina Gigot, who with her brother, Marc, manages a large livestock and crop operation out of Garden City, Kan. Virtually everything grown on their farm is for silage, hay or pasture to support either their feedyard, dairy or grazing.

Gigot said they considered the WCA program after studying information they obtained from the 2018 Ogallala Summit. “We knew we needed better water conservation,” she said. “We needed to raise corn and other crops in sandy soils with less water.”

Consistency was essential to their WCA. They switched pumping from 8 gallons per acre to about 4. The switch worked. “We took 25 percent of our allocated water and banked it for the next year,” Gigot said. “We now have 1,800 acre feet of water banked. WCA has not hurt our alfalfa yields. We don’t need as much water to grow crops.”

Moisture probes had been used in their operation. WCA expanded their probe usage. “We’ve found we can obtain useful information from winter probe data,” Gigot noted. “But overall, our biggest success has been through rotation, rotation, rotation. We’re putting more carbon in the soil to help fertility.”

According to the Kansas Dept. of Agriculture, Kansas has about 50 WCA participants, with most in areas north of Garden City. Many include feedyards or ranches. Gigot warned that growers can no longer farm like their ancestors.

“We need to share the water. We need to keep changing our practices and use less water,” Gigot explained, encouraging more producers in southwestern Kansas to consider a WCA program.

Master Irrigator programs also help producers get more out of their water. Brandy Baquera of the Colorado Master Irrigator program said the comprehensive educational course serves irrigators on the Republican River Basin. Modeled after a Master Irrigator system in Dumas, Texas, the program partners with the Natural Resources Conservation Service to help growers obtain federal Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) funding to improve water management systems.

Graduates learn about irrigation system audits, pump efficiency upgrades and other vital segments of irrigation. “We have 4,000 high-capacity wells in the region,” Baquera said. “We’ve found that using less water doesn’t necessarily mean lower yields. We use new technology as well as old practices growers may not know about.”

She said one class on system audits provided a bonus for one grower who “learned he could go home and save $10,000 with one easy change in his system. We learn we can conserve.”

Summit panel member Robert Hagevoort, New Mexico State University dairy specialist, said many dairies are stretching their water by recycling it.

“Cows are here to stay,” he said. “They do well in the dry desert climates like New Mexico and West Texas. We need to use the best [irrigation] technology to improve dairy efficiency and sustainability.

“That can be through adjusting flush systems, hose sizes and recycling water used for cooling, cleaning or irritating purposes – possibly using water three times. A lot of good things are already happening.”

Ben Holland, a research scientist with Cactus Feeders, said Cactus’ 10 High Plains feedyards are in the Ogallala’s most vulnerable levels with declining water.

“Our farmland around feedyards should be for producing grain,” he said. “But maybe we can use that supplemental irrigation to transition toward pasture. Pasture is not a bad thing. Watering to establish a pasture can be done with between two to five supplemental irrigations a year.”

He pointed out the benefits of watering only half circles in a center pivot system. “Watering a half circle limits expenses on seed and fertilizer to get the most out of water,” Holland said. “But what about the other half circle? It’s not best to plow it and let blow away,” and a dryland cover crop can help when those acres are rotated in as a row crop.

Holland acknowledged the benefits of working with university Extension to establish conservation techniques. “Extension is very helpful,” he said. “Also, we should work to educate cattle and crop associations we’re part of. Remind members that water conservation is important. In the Texas Cattle Feeders Association [for example], there is discussion of water recycling programs in feedyards.”

C.E. Williams, general manager of the Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District in White Deer, Texas, saluted producers and others for their acceptance of “smart” technology.

“Most farms have smartphone technology to know when their irrigation goes down,” he said. “This prevents downed equipment from running several hours [and wasting valuable water]. This is continual improvement rather than just sustainability.

“We’re dealing with a diminishing water supply, so continued improvement is essential. Farmers must adapt to changes to move irrigated agriculture forward. We need to think about bushels or pounds per applied irrigation water.”

A farm’s conservation plan may impact its financing, said Adam Borcya, a long-time ag lender in Cozad, Neb. With the chance for greater federal climate-related farm programs, growers “may need a climate risk analysis” when they visit their banker, Borcya said.

“Producers are learning to get better use of their water, even in areas of abundant water,” he said. “One local grower used 11 inches of irrigation and still made 200-bushel corn. More are learning they can produce the same with less water.”

TX 4-H2O Ambassadors

There’s a challenge to get more young people involved. It’s being met with local, regional, state and national programs to reach school children young and old. One proven plan is the TX 4-H2O Ambassadors program offered through Texas A&M AgriLife.

Established in 2017, 4-H2O educates youth about water resources in Texas. Every spring, up to 30 high school students are selected to participate in a summer 4-H2O Leadership Academy tour. Students travels eight days and more than 2,200 miles. They learn how water is collected, conveyed, treated, conserved and managed to meet the needs of people and economy.

“This is a way to move from talk to action,” said AgriLife’s David Smith, program leader. “We need to make the investment in young people who make an investment in agriculture. These internships are a great way to get them involved.”

In Lubbock, Texas, the High Plains Water District runs a program to help fifth graders learn about water’s use in agriculture and how to conserve it.

“We’re also seeing an interest in conservation among more domestic well-water users,” said the water district’s spokesperson, Katherine Drury,

a Summit participant. “One of the biggest challenges is keeping momentum up. We encourage people to follow us on social media and use our online resources.”

The summit was concluded with a message from Macy Downs, a 4-H’er from Plains, Texas, who worked to educate others on the Ogallala throughout her high school years. She is now a student at West Texas A&M University in Canyon.

“Generation Z is often diversified more than other age groups,” she said of her own generation. “But our diversities are our greatest asset [in conservation] because the Ogallala is so diverse. We are out here dreaming of doing your jobs. If you invest in us and support your local youth programs, we can have our voices heard. If the Ogallala has a chance to survive, you have to invest in us.”

For more information on the Ogallala and water conservation at the farm, dairy, ranch or feedyard, visit your regional water conservation district, Extension office, or go online at www.ogallalawater.org. For more on Kansas WCA go to www.agriculture.ks.gov/divisions-programs/dwr/managing-kansas-water-resources/wca.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]