By Patti Wilson, Contributing Editor

“Every breed of livestock has at least one valuable feature

that is worth preserving.”

– Harlan Ritchie, Ph.D., Professor of Animal Science,

Michigan State University, and Beef Cattle Extension Specialist

Have you ever sat on a tractor for hours, drove your pickup to a place three counties away or drifted off into thought while pitching out the calving shed? These are times when I think of the incredible changes that have happened in livestock production during my lifetime.

Finding various breeds of any species fascinating, I’ve been disappointed to watch the drastic overhaul of our nation’s pork industry. A healthy number of purebred breed associations once dotted our landscape. Although I am sure that some still exist, they have mostly been forced into consolidation, maintaining enough efficiency to justify an office. Up until the 1980s, every farm up and down any rural road raised hogs – they were called the “mortgage lifters.” Those farms are mostly gone.

Now, I am not against progress, and I understand the need for pork products to be consistent in size and taste. I know that packers need to know they have a steady and constant supply of hogs coming into the plant. Various diseases, mostly virus-borne, have also had serious repercussions as to how hogs are now raised in the United States. I still, somehow, wonder how our nation’s sow herd has turned into a cookie-cutter industry – get big or get out.

Likewise, the poultry people have gone the same route, only faster. The majority of both hogs and chickens are now a mix of breeds specifically designed for uniformity, productivity and the ability to live in confinement building units. You know where I’m going with this; let’s not allow the same thing to happen with our cattle.

We have a different business model

University of Nebraska Extension educators tell us (at grazing schools, for example) that this trend is possible in cattle production, although it will be a long time before it reaches the level of the pork and poultry industries. Cattle require too much capital (land) and too much time from gestation to plate. As compared to smaller animals, this inefficiency is burdensome.

Let’s embrace the differences

Hogs and chickens may be put in a building in Alaska or Alabama, and live under similar circumstances. Cattle cannot. Therefore, a very wide difference in breed makeup is seen worldwide, much having to do with climate. In the United States alone, we are frigid in the north and tropical in the south. We’re wet in the east and dry in the west.

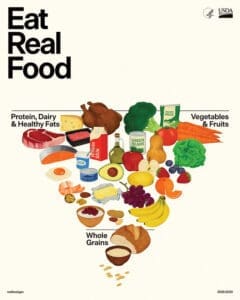

Feedstuffs vary as much as your imagination can handle. What’s the result? Cattle will eat almost anything and turn it into protein. From swamp grasses in Florida to vegetable peelings in California, cattle of whichever breed you need are there to fit the bill.

There is, as we know, a push to supply Choice, high-quality, corn-fed beef to a major share of consumers. A couple very successful breed associations are doing a wonderful job promoting branded beef to a lot of people. Kudos to them for increasing value in our product and giving us an opportunity to better ourselves. Let’s remember that there’s also room for, and a need for, other cattle that fit very specific niches along the production line.

How did this all start?

Another applicable quote from Ritchie is, “When the needs of the animal industry change over time, genetic diversity is a valuable, and for the [sic] matter, a necessary asset.”

Environment is an inescapable fact for every one of us, and the domestication of cattle was accelerated by place and need. Beginning with the taming of the Aurochs 5,000-10,000 years ago, cattle underwent dramatic physical changes quickly, according to Ritchie’s Breeds of Beef and Multipurpose Cattle. Distinct breeds began to emerge in the late 1700s, tied to the industrialization of Europe. A sharply larger human population began to migrate from rural areas into towns as mechanization accelerated the growth of factories.

“More than any other single factor, the need to feed the workers of the newly created mills and factories was responsible for the advent of modern breed and breeding practices,” he writes. Ritchie goes on to say that the Industrial Revolution spawned a cattle revolution.

This means, realistically, we can look at today’s composite meat animals as a step in the necessary reshuffling of genetic material, shaping livestock to better fit our needs. We need only to remember not to lose any valuable genetic material along the way.

British and Continental breeds

A fellow named Robert Bakewell may be considered the Mendel of livestock. (Gregor Mendel was a monk in Austria who worked with peas to discover the laws of inheritance.) Bakewell’s principle, developed in the latter part of the 1700s, was “like begets like” and, as Mendel, he was criticized and ostracized for his work. Eventually, the Englishman was vindicated by his roaring success in the development of British breeds of beef cattle and sheep. Bakewell’s methods of locking in the desirable genes was so thorough that he changed the face of the livestock industry in England and Scotland. He was considered strange, a rogue thinker, what we might call “one bubble off plumb.” He was, in fact, a genius.

As the British refined breeding practices, so did Continental Europe. The Netherlands, for example, gravitated toward dairy cattle. Much of the rest of Europe developed the heavy-boned “Continental” breeds that made their way to the United States in the 1970s and ‘80s. I can tell you from firsthand experience, it was an exciting time when the exotics arrived.

Bos indicus

Eared cattle vary greatly; they are as numerous in breed as the British and Continental types. Breaking genetically from colder-climate cattle before domestication began, the Bos indicus gravitated to the tropics and were grown, diversified and developed into the cattle we use today in the southern United States. They are a valuable, stable part of our cattle industry.

As we move forward with technologies, production methods and new efficiencies, let’s not forget the painstaking labor that has gone into the genetics we have developed over the past several centuries. There’s a lot of good out there.